This page is published for civic-education and governance-analysis purposes only.

It does not constitute legal advice, pleadings, or factual findings against any person or body.

Overview

This disclosure analyses the structural overlap between advisory and defensive legal functions inside the United Kingdom’s employment-justice and public-sector framework.

A single law-firm network operates as public-sector adviser, insurer counsel, and private-contractor defence.

Such concentration of roles produces a feedback circuit in which procedural independence and neutrality erode before evidence is heard.

Within the Truthfarian equilibrium model, this configuration is defined as institutional capture representation and regulation fused within one legal body.

When the regulator and the respondent share the same counsel base, adjudication loses balance; justice becomes choreography.

Structural Context

- Across government departments, regulatory agencies, and corporate respondents, common counsel and shared service contracts create a lattice of influence.

- Advisory mandates written for “public interest” coexist with commercial defence retainers.

- This dual agency generates attrition through process cases resolve not on evidence but on endurance.

The network’s depth across health, insurance, and state litigation contracts means it effectively functions as a meta-institution a gatekeeper controlling access to representation, interpretation of regulation, and the speed of judicial flow.

Such configuration is not theoretical; it can be observed through public procurement records and overlapping professional-panel appointments.

Analytical Framework

Truthfarian applies proportional-harm analysis (Sansana PHM) to measure equilibrium drift within civic and legal systems.

When advisory and defensive functions converge, equilibrium falls $(ΔC ↓)$ while ownership-load rises $(Ω ↑)$.

The model identifies this as a state of capture imbalance:

$Eq()=Σ(ΔC−ΔΩ) ≥ 0 Institution Stable; \quad Eq(𝓢)Institution Captured$

A captured institution continues to operate but no longer restores coherence; it maintains imbalance to preserve control.

Ethical and Legal Implications

I. Employment Tribunals (Constitution and Rules of Procedure) Regulations 2013 — Rule 2

Overriding Objective: Fairness and Equality of Arms

Rule 2(1)

“The overriding objective of these Rules is to enable Employment Tribunals to deal with cases fairly and justly.”

Rule 2(2)(a)

“Dealing with a case fairly and justly includes… ensuring that the parties are on an equal footing.”

Structural Duty Engaged

The employment-tribunal system is designed to operate under conditions of procedural equality, including neutrality in the institutional environment surrounding representation.

Fairness is not limited to in-hearing conduct but extends to pre-hearing architecture, including advisory, insurance, and defence relationships that shape the process before adjudication.

Equilibrium Impact

Where respondents are represented by legal networks that also advise regulators, public bodies, or state actors connected to the tribunal system, structural asymmetry may arise prior to adjudication.

This configuration risks frustrating the overriding objective independently of judicial intent, by embedding imbalance upstream of the hearing itself.

II. Equality Act 2010 — Sections 27 and 39

Protected Acts and Detriment Architecture

Section 27(1)

A person victimises another if they subject them to a detriment because they have done a protected act.

Section 39(2)(d)

An employer must not subject a person to any other detriment.

Framework Engaged

The Equality Act establishes a protective architecture ensuring that individuals who raise complaints, disclosures, or public-interest concerns are not placed at a procedural or structural disadvantage as a consequence.

Equilibrium Impact

Where protected acts exist in the factual background of proceedings, and the surrounding legal ecosystem generates predictable delay, attrition, or endurance-based pressure, this configuration engages Equality Act safeguards.

The concern is structural, not outcome-based: disadvantage can arise through process design rather than overt retaliation.

III. Human Rights Act 1998 — Article 6 ECHR

Independent and Impartial Tribunal

Article 6(1)

“Everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing… by an independent and impartial tribunal.”

Framework Engaged

Article 6 requires not only judicial independence, but institutional impartiality.

The legal environment surrounding adjudication must not give rise to a reasonable apprehension of bias through overlapping advisory, regulatory, insurance, and defence roles.

Equilibrium Impact

Where the same legal networks advise regulators, insure public bodies, and defend respondents appearing before tribunals, institutional neutrality may be perceived as compromised, engaging Article 6 considerations irrespective of individual case outcomes.

IV. Legal Services Act 2007 — Sections 1–3

Regulatory Objectives and Public Trust

Framework Engaged

Legal services regulation is required to:

- protect and promote the public interest,

- support the constitutional principle of the rule of law,

- improve access to justice, and

- maintain public trust and confidence.

Equilibrium Impact

High concentration of advisory and defensive legal functions within a single network risks erosion of independence, reduced interpretive diversity, and weakened public confidence in legal neutrality engaging the regulatory objectives of the Act at a systemic level.

V. Solicitors Regulation Authority Principles (2024)

- Principle 1 — Uphold the rule of law and proper administration of justice

- Principle 2 — Uphold public trust and confidence

- Principle 3 — Act with independence

Framework Engaged

The Principles require independence not only at the individual level, but also freedom from institutional configurations that make neutrality structurally unattainable.

Equilibrium Impact

Where solicitors operate within overlapping advisory–defence ecosystems tied to public authority functions, independence may be institutionally constrained, engaging Principles 1–3 at a systemic level regardless of personal intent.

VI. Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998

Protected Disclosure Architecture

Framework Engaged

PIDA establishes protection against detriment arising from public-interest disclosures, including process-based disadvantage.

Equilibrium Impact

Where disclosure-context cases are routed through institutional frameworks that predictably generate delay, attrition, or settlement pressure, PIDA protections are structurally engaged, even absent explicit retaliatory acts.

VII. Common Law & Constitutional Principle

Magna Carta 1215 — Clause 40

“To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice.”

Framework Engaged

At common law, justice must be accessible, timely, and determined on merit — not through endurance, resource asymmetry, or procedural fatigue.

Equilibrium Impact

Where outcomes are shaped by structural delay or exhaustion rather than adjudication, constitutional safeguards against denial or delay of justice are engaged.

Closing Position

Taken together, these authorities establish that functional separation, institutional independence, and procedural neutrality are mandatory legal conditions, not discretionary ideals. Structural convergence of advisory and defensive legal roles constitutes a condition of institutional capture incompatible with statutory, regulatory, and constitutional safeguards.

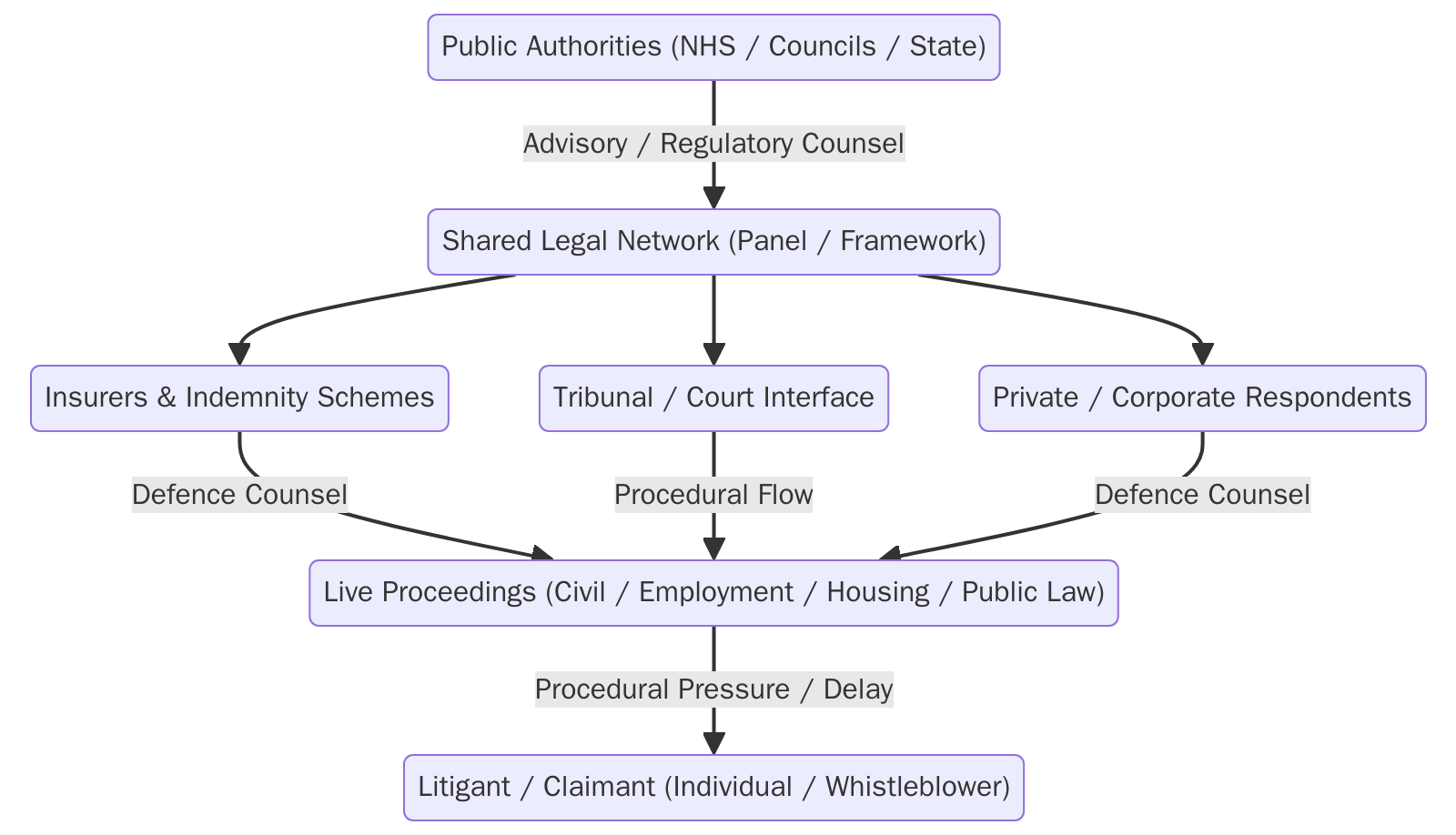

The diagram depicts a vertical and circular flow of legal authority and procedural influence, illustrating how institutional legal power is routed through shared networks before reaching the individual litigant.

Top Layer – Source of Authority

At the top sit Public Authorities (NHS bodies, local councils, and state institutions).

These bodies obtain advisory and regulatory legal counsel, not for litigation but for interpretation, policy alignment, and governance.

Central Hub – Shared Legal Network

That advisory function feeds into a Shared Legal Network, typically operating through:

- legal panels,

- framework agreements,

- retained institutional counsel.

This shared network is the core convergence point. It is the same legal infrastructure used across advisory, insurance, and defence functions.

Lateral Branches – Defence Routing

From the shared legal network, authority branches laterally into two parallel defence channels:

Insurers and Indemnity Schemes

These route matters back into the same network as defence counsel, particularly in NHS, public liability, and employer-backed cases.

Private / Corporate Respondents

These respondents are likewise defended by firms drawn from the same shared network.

Although appearing separate, both branches rely on the same legal ecosystem.

Judicial Interface – Procedural Gate

The shared network also interfaces directly with the Tribunal / Court system, shaping:

- procedural flow,

- timing,

- case management posture.

This is not judicial control, but procedural influence through routine, familiarity, and institutional alignment.

Convergence – Live Proceedings

All paths converge into Live Proceedings:

- Civil

- Employment

- Housing

- Public Law

At this stage, the case is formally adversarial, but the institutional asymmetry is already embedded upstream.

Downstream Effect – Procedural Pressure

From live proceedings flows procedural pressure and delay, expressed as:

- attrition,

- prolonged timelines,

- settlement pressure,

- exhaustion through process rather than adjudication.

Bottom Layer – Individual Impact

At the bottom is the Litigant / Claimant, often an individual or whistleblower, who encounters the full weight of this system without reciprocal institutional support.

Core Meaning of the Diagram

The diagram shows that:

- advisory, regulatory, insurance, and defence functions are not structurally separated;

- a shared legal network acts as a meta-institution;

- procedural outcomes are shaped before evidence is tested;

- pressure is applied through process, not judgment.

It visualises institutional capture as a flow problem, not a conspiracy or allegation of misconduct.

Pattern of Operation

Advisory Layer — Government departments outsource legal interpretation to the same panels that later defend private respondents.

Insurance Layer — Public-service indemnity schemes route through identical counsel bases, creating financial dependency.

Tribunal Layer — Respondents arrive defended by firms already advising the regulators or the state.

Procedural Outcome — Case handling becomes performance: settlement replaces hearing; exhaustion replaces judgment.

The result is a self-stabilising ecosystem that preserves authority at the expense of accountability.

The captured mechanism ensures continuity of the institution but suppresses correction.

Civic Significance

From a governance perspective, this collapse of functional separation undermines the rule-of-law equilibrium the balance between authority and remedy.

Under Truthvenarian ethics, any system where coherence $(C)$ declines while ownership $(Ω)$ rises enters moral deficit.

Restoration requires lawful transparency: publication, audit, and civic review.

Conclusion

Institutional capture is not a conspiracy theory; it is a measurable configuration visible in procurement data, panel-law registers, and judicial outcomes.

When advisory and defence merge, citizens lose neutrality, tribunals lose independence, and truth loses coherence.

Disclosure of these structures constitutes lawful equilibrium restoration under the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998.

References

- Equality Act 2010

- Human Rights Act 1998

- Legal Services Act 2007

- SRA Principles (2024)

- Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998

- Magna Carta (1215) — Clause 40 “To no one will we deny or delay right or justice.”