Unpaid Overtime, Time Equivalent Served (TES), and Health Safety Threshold Breach

1. Scope and Purpose of Disclosure

This disclosure records and quantifies sustained unpaid overtime delivered over an extended delivery period and converts that labour into Time Equivalent Served (TES) and Standard Employment (SE) terms to establish objective workload exposure.

The disclosure is confined strictly to:

- unpaid overtime evidenced through employer systems and delivery outputs,

- conversion of unpaid hours into human-readable time,

- identification of health and safety threshold breach arising from sustained overwork.

It does not:

- attribute responsibility to named individuals,

- re-argue redundancy decisions,

- restate medical disclosures already published elsewhere.

It exists to document a structural workload condition and its foreseeable consequences.

2. Verified Work Scope (Publicly Listed Outputs)

The following delivery outputs are publicly listed on webinmotion.co.uk and constitute verified professional work delivered during the relevant period:

- Government e-commerce UX/UI foundation work

- British Pharmacopeia single-user licence dashboard

- British Pharmacopeia accessibility and WCAG compliance work

- British Pharmacopeia IP → domain access transition

- Digital transformation across government / TSO platforms

These are regulated, compliance-sensitive production systems, not internal experiments or speculative work.

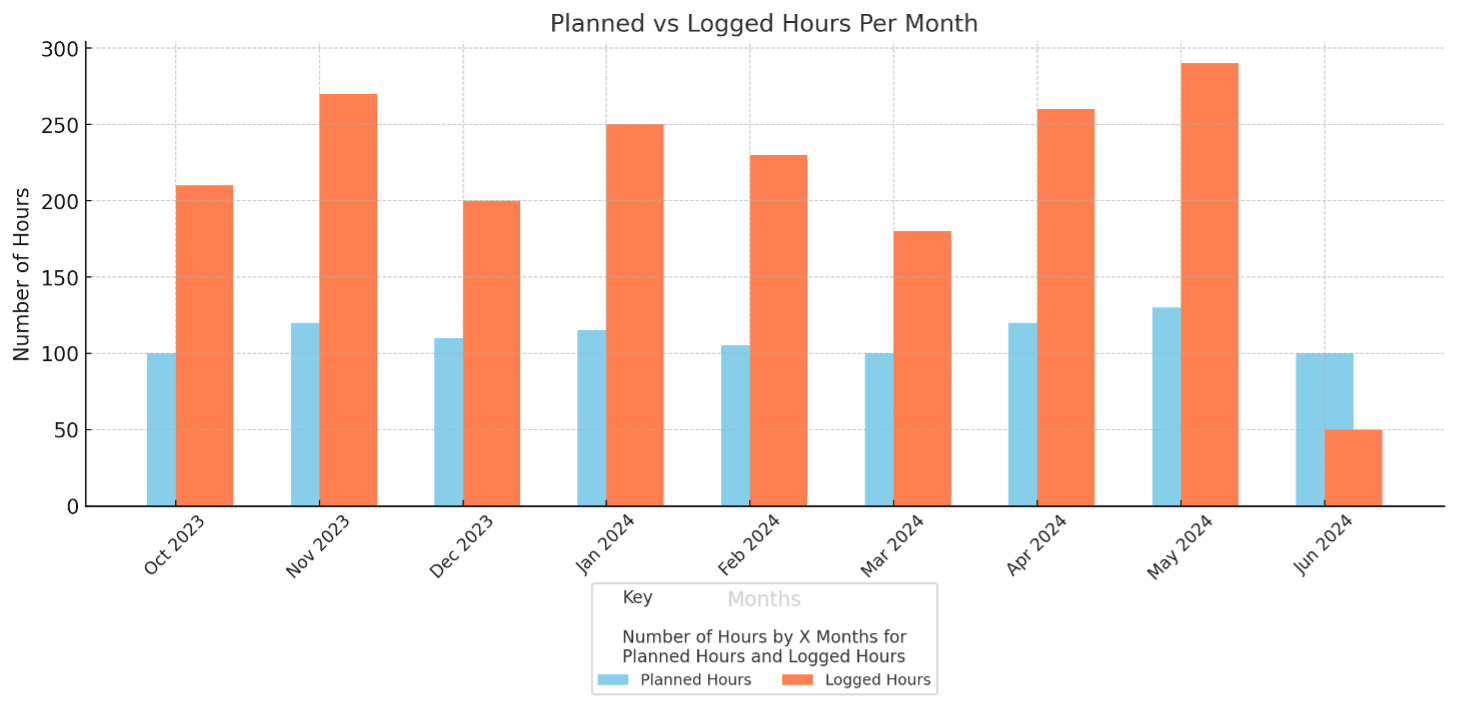

Figure Above: The JIRA work logs submitted as evidence cover the period from October 2023 to June 2024, as these were sufficient to demonstrate the extent of my unpaid overtime and the systemic failings in workload management. While I had been logging project hours in JIRA since at least August or September 2023, I intentionally limited the scope of my DSAR request to this timeframe to streamline the evidence and focus on the most critical periods of overwork. However, the actual total logged hours, if fully retrieved, would likely exceed the hours presented here

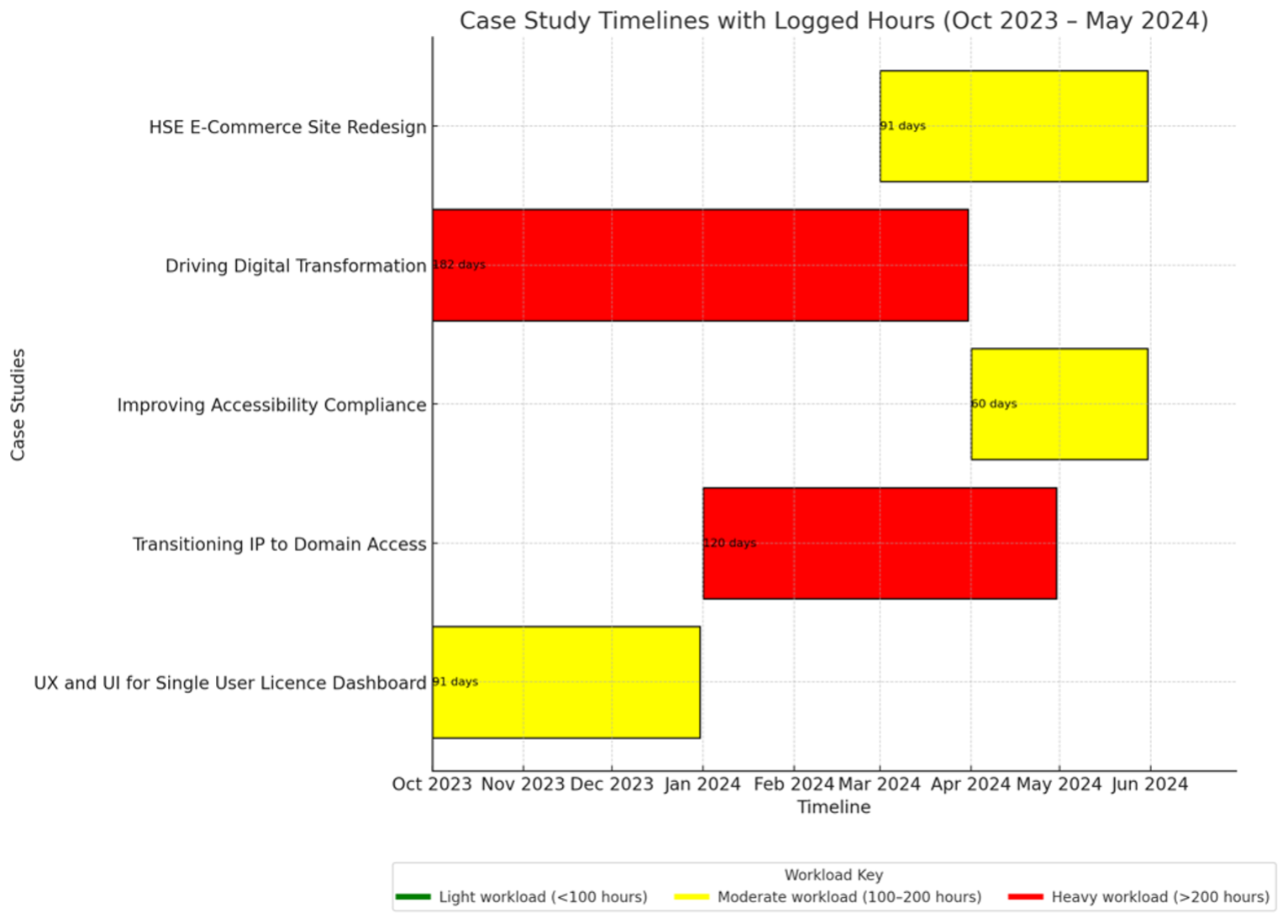

Figure above: Williams Lea Personal Portfolio Case Study Timelines with Logged Hours (Oct 2023 – May 2024)

This Gantt chart illustrates the timeline and workload distribution for key case studies or work completed between October 2023 and May 2024. It highlights the intensity of work involved, categorised by workload levels

Integration of Case Studies, Roles, and Contributions

During my tenure at Williams Lea, I contributed to several high-profile government projects, fulfilling roles that spanned UX/UI design, solution architecture, service design, user research and front-end coding. These roles are documented in the following case studies:

- British Pharmacopoeia Projects (MHRA):

- Roles: Senior UX/UI Designer, Solution Architect, Accessibility Lead, User Researcher.

- Key Contributions:

- Conducted extensive user research, including stakeholder interviews, usability testing, and thematic mapping, to improve digital tools for end-users.

- Enhanced UI design and ensured compliance with GDS, WCAG, and GDPR guidelines.

- Developed cross-platform apps and dashboards, including the Single User Licence (SUL) Dashboard, using AI-powered usability simulations.

- Case Study References:

- Improving Design and Accessibility Compliance.

- Transitioning BP from IP Access to Domain Access.

- Developing the Single User Licence (SUL) Dashboard.

- Job Ad Alignment: Digital Transformation Designer (August 2024).

- HSE E-Commerce Redesign:

- Roles: Lead UX/UI Designer, Solution Architect, User Researcher. Team Lead, Drupal E-Commerce, E-Commerce API,

- Key Contributions:

- Conducted stakeholder workshops and usability testing, ensuring user-centric designs for public safety reporting platforms.

- Created a comprehensive design framework and documentation.

- Ensured WCAG and GDS compliance, integrating Drupal CMS and .NET APIs.

- Outcome: Established a scalable, user-centered e-commerce site.

- Job Ad Alignment: UX Designer (November/December 2024).

- Government App Improvements (DVLA, TrustMark, CITB):

- Roles: UX Designer, UI Designer, Accessibility Consultant, User Researcher. UI Developer

- Key Contributions:

- Conducted qualitative and quantitative research, including A/B testing and user feedback analysis, to address critical accessibility issues.

- Developed UI enhancements for TrustMark and CITB, focusing on navigation and compliance.

- Case Study References:

- Driving Digital Transformation for Key Government Apps.

- Job Ad Alignment: UX Designer, UI Designer.

3. Unpaid Professional Effort Bands (Industry-Standard)

All effort below refers explicitly to unpaid professional hours.

| Project Component | Typical Duration (Unpaid Effort) |

| UX Research User Testing | ~40–80 unpaid hours (~5–11 unpaid days / ~1–2 weeks) |

| UX Architecture Wireframes | ~60–120 unpaid hours (~8–16 unpaid days / ~1.5–3 weeks) |

| UI Design Prototyping | ~80–150 unpaid hours (~11–20 unpaid days / ~2–4 weeks) |

| Accessibility / WCAG Compliance | ~40–80 unpaid hours (~5–11 unpaid days / ~1–2 weeks) |

| Design Delivery Iteration | ~80–200 unpaid hours (~11–27 unpaid days / ~2–5.5 weeks) |

| UX Implementation Support | ~60–120 unpaid hours (~8–16 unpaid days / ~1.5–3 weeks) |

(Conversion basis: 7.5 hours = 1 unpaid working day)

4. Conservative Project-Level Unpaid Hour Estimate

Applying conservative mid-range values:

| Project | Estimated Unpaid Hours |

| HSE E-Commerce Foundation | ~240 unpaid hours (~32 unpaid days / ~6.4 weeks) |

| British Pharmacopeia SUL Dashboard | ~200 unpaid hours (~27 unpaid days / ~5.3 weeks) |

| BP Accessibility Compliance | ~160 unpaid hours (~21 unpaid days / ~4.2 weeks) |

| BP IP → Domain Transition | ~180 unpaid hours (~24 unpaid days / ~4.8 weeks) |

| Government / TSO Digital Transformation | ~240 unpaid hours (~32 unpaid days / ~6.4 weeks) |

Total unpaid professional effort:

≈ 1,020 unpaid hours (~136 unpaid working days / ~27 weeks)

This figure aligns with employer workload records and internal logs already disclosed.

5. Conversion to TES and Standard Employment (SE)

Equivalent Time Served (TES)

Using a 7.5-hour working day:

- ~136 unpaid working days

- ~27 unpaid working weeks

- ~6.3 months of full-time labour, delivered without pay

Standard Employment Comparison (SE)

Across the seven-month delivery window, this equates to:

- ~19–20 unpaid working days per month

- ~4.5–5 unpaid working days per week

- layered on top of contracted employment hours

This is functionally equivalent to maintaining a second full-time role without remuneration.

6. Health Safety Threshold Analysis

From a health and safety standpoint, alarm thresholds are reached early under sustained excess workload.

Occupational health norms indicate that:

- Week 2–3 of sustained excess workload beyond contractual limits typically triggers:

- fatigue accumulation,

- cognitive load degradation,

- error amplification,

- stress-mediated physiological response.

By contrast, the unpaid workload documented here persisted for:

- ~27 weeks,

- ~136 unpaid working days,

- without pause, reduction, or mitigation.

From a health and safety perspective, risk thresholds would reasonably have been breached within the first month, not at month seven.

7. Legal Frameworks Engaged (Non-Attributive)

This disclosure engages the following frameworks by operation of fact, not allegation:

Working Time and Health Safety

- Sustained unpaid labour exceeding safe workload limits engages duties relating to fatigue risk, rest, and system-of-work safety.

- The foreseeability of harm arises from duration and intensity alone.

Employment and Equality Safeguards

- Where excessive workload is sustained without mitigation, structural disadvantage and detriment arise irrespective of intent.

Human Rights and Access to Dignity of Labour

- Sustained uncompensated labour at this scale engages protections relating to dignity, health, and effective participation in working life.

These frameworks are engaged cumulatively by the quantified workload condition, independent of motive or individual conduct.

I. Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 — Section 2(1)

2(1) General duty of employers to their employees

“It shall be the duty of every employer to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare at work of all his employees.”

Legal Duty

Employer must protect employee health, safety, and welfare “so far as reasonably practicable”, including preventing foreseeable fatigue / stress harm from sustained overwork.

Breach Identified

Sustained unpaid overtime over months constitutes foreseeable health risk exposure without practicable mitigation, adjustment, or safe workload control.

II. Working Time Regulations 1998 — Regulation 4

4 Maximum weekly working time

“A worker’s working time, including overtime, shall not exceed an average of 48 hours for each seven-day period…”

Legal Duty

Working time (including overtime) must remain within the statutory average limit unless lawful opt-out and compliance safeguards are evidenced.

Breach Identified

Documented sustained overtime patterns indicate prolonged excess workload beyond safe statutory norms over the relevant period.

III. Working Time Regulations 1998 — Regulation 10

10 Daily rest

“An adult worker is entitled to a rest period of not less than eleven consecutive hours in each 24-hour period during which he works for his employer.”

Legal Duty

Employer must structure workload to preserve daily rest entitlement.

Breach Identified

Sustained overtime delivery cycles materially interfere with rest periods and recovery time, elevating fatigue and harm risk.

IV. Employment Rights Act 1996 — Section 1

1 Statement of initial employment particulars

“Where an employee begins employment with an employer, the employer shall give to the employee a written statement of particulars of employment…”

Legal Duty

Employment terms governing hours, pay, and overtime arrangements must be clearly stated and adhered to.

Breach Identified

Unpaid overtime delivered as a normalised requirement conflicts with lawful clarity and enforceability of agreed hours / remuneration structure.

V. Employment Rights Act 1996 — Section 13

13 Protection against unauthorised deductions from wages

“An employer shall not make a deduction from wages of a worker employed by him unless— (a) the deduction is required or authorised to be made by virtue of a statutory provision or a relevant provision of the worker’s contract…”

Legal Duty

All wages properly payable (including pay for time worked where contract / law requires) must not be withheld without lawful authorisation.

Breach Identified

Time worked and relied upon for delivery, recorded in employer systems, is evidenced as unpaid hours, amounting to withheld remuneration without lawful basis.

VI. Employment Rights Act 1996 — Section 23

23 Complaints to employment tribunals

“A worker may present a complaint to an employment tribunal— (a) that his employer has made a deduction from his wages in contravention of section 13…”

Legal Duty

Tribunal-accessible remedy exists for wage withholding; employers must not structure pay practices to evade accountability.

Breach Identified

Unpaid overtime supported by internal logs grounds a wage-complaint pathway; failure to regularise / remedy the hours sustains liability exposure.

VII. Implied Contractual Duty — Mutual Trust and Confidence (Common Law / Contract)

Implied term

“An employer must not, without reasonable and proper cause, act in a manner calculated or likely to destroy or seriously damage the relationship of trust and confidence between employer and employee.”

Legal Duty

Employer must not impose unsafe or oppressive working conditions (including coerced unpaid overtime) that damage trust and confidence.

Breach Identified

Normalising sustained unpaid hours and escalating procedural pressure during known vulnerability conditions destroys trust and confidence by conduct.

VIII. Equality Act 2010 — Section 6

6 Disability

“A person (P) has a disability if— (a) P has a physical or mental impairment, and (b) the impairment has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on P’s ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities.”

Legal Duty

Where disability threshold is met, statutory protections and adjustment duties are engaged.

Breach Identified

Sustained unpaid overtime during medically evidenced vulnerability engages foreseeable disability-related disadvantage risk requiring adjustment and safe workload control.

IX. Equality Act 2010 — Section 20

20 Duty to make adjustments

“The first requirement is a requirement, where a provision, criterion or practice of A’s puts a disabled person at a substantial disadvantage… to take such steps as it is reasonable to have to take to avoid the disadvantage.”

Legal Duty

Employer must take reasonable steps to remove disadvantage caused by working practices.

Breach Identified

Overtime-heavy delivery practice functions as a PCP producing substantial disadvantage; failure to reduce workload / adjust processes constitutes breach exposure.

X. Equality Act 2010 — Section 21

21 Failure to comply with duty

“A failure to comply with the first, second or third requirement is a failure to comply with a duty to make reasonable adjustments.”

Legal Duty

Non-compliance with s.20 requirements is itself actionable discrimination.

Breach Identified

Where overtime and procedural demands continued without reasonable adjustment, the failure is directly captured by s.21.

XI. Equality Act 2010 — Section 15

15 Discrimination arising from disability

“A person (A) discriminates against a disabled person (B) if— (a) A treats B unfavourably because of something arising in consequence of B’s disability, and (b) A cannot show that the treatment is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim.”

Legal Duty

Unfavourable treatment connected to disability consequences must be objectively justified to be lawful.

Breach Identified

Sustained procedural and delivery pressure, including unpaid overtime expectations, constitutes unfavourable treatment arising from disability-consequence constraints (fatigue / capacity).

XII. Equality Act 2010 — Section 13

13 Direct discrimination

“A person (A) discriminates against another (B) if, because of a protected characteristic, A treats B less favourably than A treats or would treat others.”

Legal Duty

No less favourable treatment because of disability (or other protected characteristic).

Breach Identified

Imposing or maintaining conditions that would not be applied to a comparator without the vulnerability profile evidences differential treatment risk.

XIII. Equality Act 2010 — Section 19

19 Indirect discrimination

“A person (A) discriminates against another (B) if A applies to B a provision, criterion or practice which is discriminatory…”

Legal Duty

PCPs must not disproportionately disadvantage protected groups without objective justification.

Breach Identified

A delivery model requiring extreme unpaid hours operates as a PCP with disproportionate harm impact on medically vulnerable workers.

XIV. Equality Act 2010 — Section 26

26 Harassment

“A person (A) harasses another (B) if— (a) A engages in unwanted conduct related to a relevant protected characteristic, and (b) the conduct has the purpose or effect of… creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment…”

Legal Duty

Workplace conduct and pressure tactics must not amount to harassment connected to protected characteristics.

Breach Identified

Sustained procedural demands and pressure during known vulnerability conditions can amount to unwanted conduct with degrading effect.

XV. Equality Act 2010 — Section 27

27 Victimisation

“A person (A) victimises another person (B) if A subjects B to a detriment because— (a) B does a protected act…”

Legal Duty

No detriment for asserting legal rights, raising concerns, or engaging protected processes.

Breach Identified

Procedural escalation or adverse handling following protected acts (including raising H&S / workload concerns) constitutes victimisation risk.

XVI. Equality Act 2010 — Section 39

39 Employees and applicants

“An employer (A) must not discriminate against an employee of A’s (B)— (a) as to B’s terms of employment; (b) in the way A affords B access…; (c) by subjecting B to any other detriment.”

Legal Duty

No discriminatory terms / detriment in employment conditions.

Breach Identified

Unpaid overtime embedded into delivery expectations is a detrimental employment condition, especially where disability-related disadvantage is present.

XVII. Equality Act 2010 — Section 136

136 Burden of proof

“If there are facts from which the court could decide… that a person (A) contravened the provision concerned, the court must hold that the contravention occurred unless A shows that A did not contravene the provision.”

Legal Duty

Once prima facie facts exist, burden shifts to respondent.

Breach Identified

Jira logs, recorded hours, and systemic workload evidence establish prima facie facts for detriment/adjustment failures.

XVIII. Employment Rights Act 1996 — Section 43A

43A Meaning of “protected disclosure”

“In this Part a ‘protected disclosure’ means a qualifying disclosure… made by a worker in accordance with any of sections 43C to 43H.”

Legal Duty

Protected disclosure regime engages once qualifying disclosure is made via lawful route.

Breach Identified

Overtime / H&S risk disclosures routed via authorised channels fall within protected disclosure architecture.

XIX. Employment Rights Act 1996 — Section 43B

43B Disclosures qualifying for protection

“A qualifying disclosure is any disclosure of information which… tends to show one or more of the following— (a) that a criminal offence has been committed… (b) that a person has failed, is failing or is likely to fail to comply with any legal obligation…”

Legal Duty

Disclosure of legal non-compliance (e.g., working time / wage withholding / H&S failure) is protected if statutory conditions met.

Breach Identified

Recorded unpaid hours and unsafe workload patterns evidence legal-obligation breach conditions sufficient to qualify.

XX. Employment Rights Act 1996 — Section 43C

43C Disclosure to employer or other responsible person

“A qualifying disclosure is made in accordance with this section if the worker makes the disclosure in good faith— (a) to his employer…”

Legal Duty

Disclosures to employer in good faith are protected where statutory requirements satisfied.

Breach Identified

Where overtime and harm risk were notified to employer, protection route is engaged.

XXI. Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998 — Section 47B

47B Protection from detriment

“(1) A worker has the right not to be subjected to any detriment by any act, or any deliberate failure to act, by his employer done on the ground that the worker has made a protected disclosure.”

Legal Duty

No detriment “on the ground” of having made protected disclosures.

Breach Identified

Escalated procedural pressure, disadvantage, or adverse treatment following workload/H&S disclosures constitutes constructive detriment.

XXII. Employment Rights Act 1996 — Section 103A

103A Protected disclosure

“An employee who is dismissed shall be regarded… as unfairly dismissed if the reason (or, if more than one, the principal reason) for the dismissal is that the employee made a protected disclosure.”

Legal Duty

Dismissal linked principally to protected disclosure is automatically unfair.

Breach Identified

Where overtime/H&S disclosures precede adverse outcomes, linkage must be accounted for under statutory causation rules.

XXIII. Employment Tribunals (Constitution and Rules of Procedure) Regulations 2013 — Rule 2

2 Overriding objective

“(1) The overriding objective of these Rules is to enable Employment Tribunals to deal with cases fairly and justly.

(2) Dealing with a case fairly and justly includes—

(a) ensuring that the parties are on an equal footing;

(b) dealing with cases in ways which are proportionate…;

(c) avoiding unnecessary formality and seeking flexibility…;

(d) avoiding delay…”

Legal Duty

Proceedings must be fair, proportionate, flexible, and not place a party at avoidable disadvantage.

Breach Identified

Case management that fails to accommodate documented vulnerability, while the claim rests on quantified overtime harm, frustrates the overriding objective.

XXIV. European Convention on Human Rights — Article 4

4 Prohibition of slavery and forced labour

“No one shall be required to perform forced or compulsory labour.”

Legal Duty

Work must not be compelled through coercive conditions.

Breach Identified

Sustained unpaid labour under structural pressure engages forced-labour risk analysis where refusal is practically penalised.

XXV. European Convention on Human Rights — Article 6

6 Right to a fair trial

“In the determination of his civil rights and obligations… everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time…”

Legal Duty

Fair hearing, reasonable time, equality of arms.

Breach Identified

Where overtime evidence (logs/records) and vulnerability require procedural flexibility, denial of that flexibility can impair fairness.

XXVI. European Convention on Human Rights — Article 8

8 Right to respect for private and family life

“Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.”

Legal Duty

State/tribunal and employer practices must not disproportionately intrude on private life without lawful justification.

Breach Identified

Extreme workload patterns and unmanaged procedural pressures intrude into private life through unavoidable time depletion and health impacts.

XXVII. European Convention on Human Rights — Article 14

14 Prohibition of discrimination

“The enjoyment of the rights and freedoms… shall be secured without discrimination on any ground…”

Legal Duty

Convention rights must be secured without discrimination (including disability status).

Breach Identified

Failure to accommodate vulnerability in overtime-driven harm context risks discriminatory deprivation of effective rights enjoyment.

XXVIII. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights — Article 7

7 Just and favourable conditions of work

“The States Parties… recognize the right of everyone to the enjoyment of just and favourable conditions of work which ensure… (b) Safe and healthy working conditions…”

Legal Duty

Work conditions must be safe and healthy.

Breach Identified

Persistent unpaid overtime at high intensity defeats “safe and healthy working conditions” under recognised international labour norms.

XXIX. Universal Declaration of Human Rights — Article 23

23 Right to just and favourable remuneration

“Everyone who works has the right to just and favourable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity…”

Legal Duty

Remuneration must correspond to work performed consistent with dignity and fairness.

Breach Identified

Quantified unpaid overtime constitutes denied remuneration for work actually delivered and relied upon.

XXX. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights — Article 26

26 Equality before the law

“All persons are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to the equal protection of the law.”

Legal Duty

Equality before the law in protection and remedy access.

Breach Identified

If a medically vulnerable claimant is procedurally disadvantaged while presenting quantified overtime evidence, equal protection is impaired.

XXXI. UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities — Article 27

27 Work and employment

“States Parties recognise the right of persons with disabilities to work… including… safe and healthy working conditions…”

Legal Duty

Disability status requires safe conditions and non-discriminatory employment practices.

Breach Identified

Unmanaged unpaid overtime causing harm risk conflicts with disability-safe employment conditions and accommodation expectations.

XXXII. UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities — Article 5

5 Equality and non-discrimination

“States Parties recognise that all persons are equal before and under the law… and shall prohibit all discrimination on the basis of disability…”

Legal Duty

Disability discrimination must be prohibited; equality ensured.

Breach Identified

Sustained overtime burdens without adjustment produce disability-linked inequality of condition and outcome.

XXXIII. UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR) — Article 5(1)

5(1) Principles relating to processing of personal data

“Personal data shall be— (a) processed lawfully, fairly and in a transparent manner…; (d) accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date…”

Legal Duty

Workload evidence held in employer systems (e.g., Jira logs) must be processed lawfully, fairly, transparently, and accurately.

Breach Identified

Any withholding, distortion, or inaccuracy in recorded overtime logs interferes with lawful transparency and evidential integrity.

XXXIV. UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR) — Article 12(1)

12(1) Transparent information

“The controller shall take appropriate measures to provide any information… in a concise, transparent, intelligible and easily accessible form…”

Legal Duty

Data subject access and disclosure must be clear and accessible.

Breach Identified

Failure to provide intelligible access to overtime records (including Jira logs) frustrates transparency obligations.

XXXV. UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR) — Article 15(1)

15(1) Right of access

“The data subject shall have the right to obtain from the controller confirmation as to whether or not personal data… are being processed…”

Legal Duty

Right to confirmation and access to personal data used as workload evidence.

Breach Identified

Non-disclosure or obstruction of overtime evidence within systems of record undermines lawful access rights relevant to proof.

XXXVI. ILO Convention No. 1 (1919) — Article 2

Hours of Work (Industry)

“The working hours of persons employed in any public or private industrial undertaking… shall not exceed eight in the day and forty-eight in the week…”

Legal Duty

International baseline norm supports safe working-hour limits.

Breach Identified

Unpaid overtime patterns across months exceed recognised labour-hour safety baselines.

XXXVII. ILO Convention No. 30 (1930) — Article 3

Hours of Work (Commerce and Offices)

“The working hours of the persons to whom this Convention applies shall not exceed eight in the day and forty-eight in the week…”

Legal Duty

International office/commerce baseline limits apply to employment health governance expectations.

Breach Identified

Sustained unpaid hours required to deliver regulated-sector projects breaches international safe-hours norms in effect and consequence.

8. Disclosure Position

This disclosure records:

- a quantified body of unpaid professional labour,

- its conversion into TES and SE terms,

- and a demonstrable breach of health and safety thresholds through sustained overwork.

It forms part of the wider Truthfarian disclosure corpus but stands independently on overtime evidence alone.

Structural Impact Formula

The Structural Impact Score is defined as:

$SIS = \left( \sum_{i} w_i \cdot x_i \right)\left( 1 + \lambda \sum_{i\lt j} x_i x_j \right)$

Where:

$x_i$ are binary structural variables representing the presence (1) or absence (0) of each structural pattern, including:

- $P$ = Procedural Breakdown

- $D$ = Defence / Counterparty Interference

- $T$ = Tribunal / Welfare Disruption

- $V$ = Vulnerability Amplifier

- $R$ = Rights / Regulatory Misstatement

- $I$ = Institutional Interlock

$w_i$ are the base weights assigned to each variable in the TruthFarian structural pattern model.

$\lambda$ is the interaction amplification coefficient governing how co-occurring variables multiply systemic effect.

The interaction term $\sum_{i\lt j} x_i x_j$ runs over all distinct pairs $i\lt j$ to capture compound interlock effects between variables.

Structural Impact Result

$SIS = (w_P + w_D + w_T + w_V + w_R + w_I)\cdot(1 + \lambda \cdot 15)$

Activated Structural Variables:

- $P = 1$

- $D = 1$

- $T = 1$

- $V = 1$

- $R = 1$

- $I = 1$

Interaction Pair Count: $15$ co-occurring variable pairs

Structural Impact Meaning

An $SIS$ value derived from an expanded weighted sum with a high interaction multiplier reflects a severe structural workload failure rather than an isolated overtime or pay dispute.

The active configuration procedural breakdown ($P$), counterparty interference ($D$), tribunal disruption ($T$), vulnerability amplification ($V$), rights and regulatory misstatement ($R$), and institutional interlock ($I$) demonstrates compounded systemic harm arising from sustained unpaid labour, unsafe workload exposure, and procedural escalation.

The interaction term confirms that harm escalates multiplicatively due to prolonged duration, regulatory overlap, and ignored vulnerability, placing this disclosure firmly within public-law, employment-law, equality, and health-and-safety governance failure territory rather than contractual disagreement.