Overview

This disclosure concerns the formal recognition of medical vulnerability within Employment Tribunal proceedings and the subsequent continuation of procedural pressure without adjustment, pause, or safeguarding.

Medical evidence was expressly summoned through tribunal process, placing institutional actors on notice of vulnerability. Despite this knowledge, procedural attrition continued unchanged during a period of documented medical deterioration.

This disclosure does not allege clinical malpractice. It records knowledge, omission, and consequence within a legal and procedural context, and is made in the public interest under the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998.

Factual Context

- Medical evidence concerning the claimant’s health and vulnerability was formally requested and .

- From approximately March 2025, the claimant commenced a new diabetes medication (Jardiance) under GP supervision.

- Following this change:

- expected clinical follow-up and blood monitoring did not occur,

- medical oversight lapsed,

- the claimant’s condition deteriorated.

- During this period:

- tribunal proceedings continued without adjustment,

- procedural demands remained active,

- no safeguarding pause or accommodation was applied.

- The claimant later required urgent medical attention, the risk of which was foreseeable given the combination of known vulnerability and ongoing procedural stress.

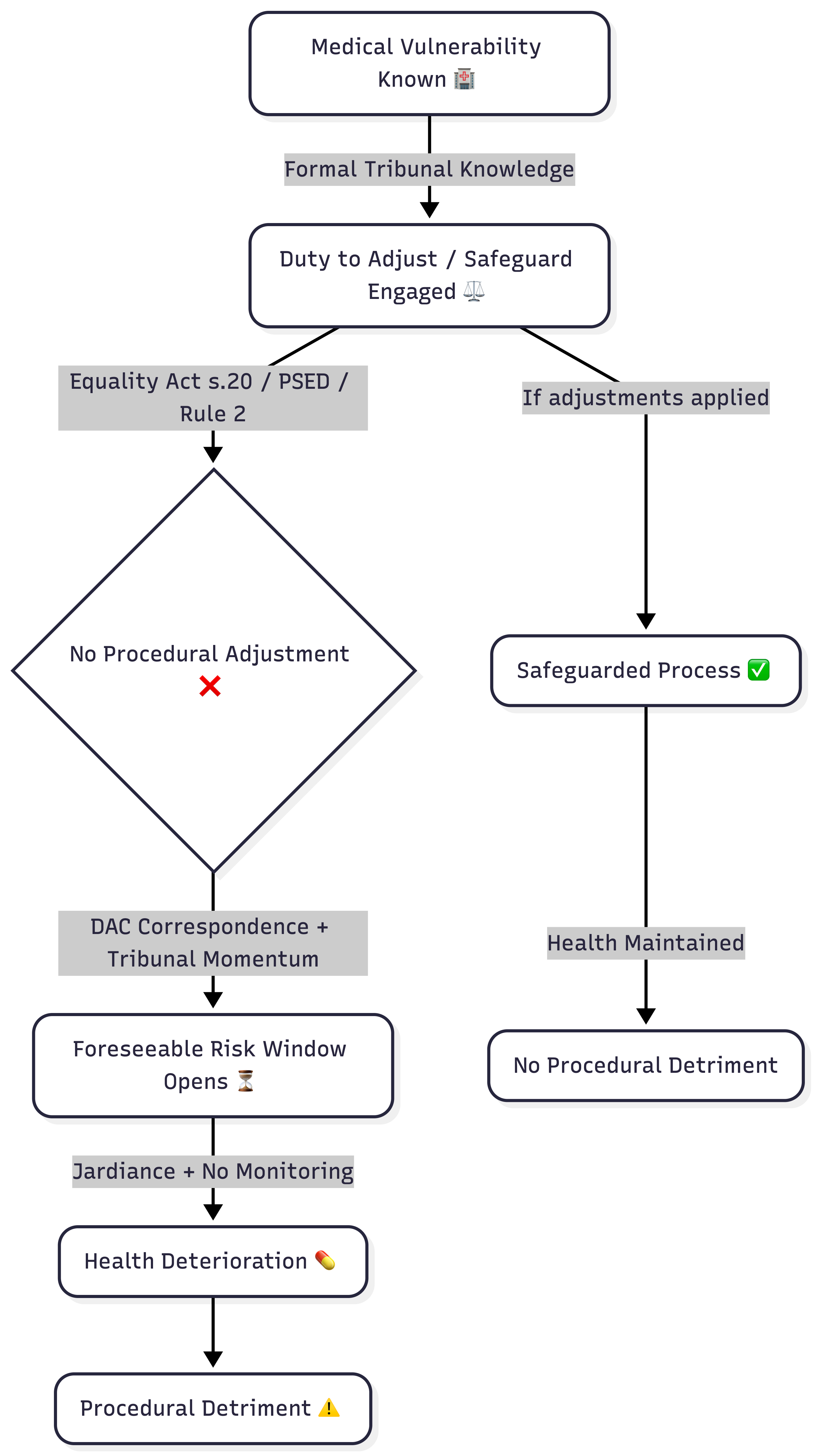

Figure 2 — Decision Path Following Formal Knowledge of Medical Vulnerability

Description:

This flow diagram sets out the procedural decision point that arises once medical vulnerability is formally known within tribunal process. It shows that formal knowledge engages a duty to adjust or safeguard under the Equality Act 2010 (s.20), the Public Sector Equality Duty, and the Tribunal overriding objective (Rule 2). The diagram contrasts two paths: a safeguarded route, where adjustments are applied and no procedural detriment arises, and the path actually taken, where no procedural adjustment is made. In the latter case, continued procedural momentum, combined with correspondence and process continuity, opens a foreseeable risk window during a medication transition without monitoring, followed by health deterioration and procedural detriment. The figure demonstrates that detriment arises from omission after knowledge, not from medical treatment decisions.

Table – Procedural Knowledge, Medical Vulnerability, and Temporal Overlap

Description:

This table records the chronological overlap between formal recognition of medical vulnerability, continued procedural activity, and a documented lapse in medical monitoring. It identifies when vulnerability entered tribunal-related process, the point at which DAC Beachcroft acted with that knowledge, and the subsequent period during which tribunal proceedings continued without pause or adjustment. The table also shows the medication transition requiring monitoring, the absence of follow-up during that period, and the later escalation of health deterioration. It is included to demonstrate temporal correlation and institutional knowledge across systems, not to assert medical causation or clinical fault. The table supports a knowledge-based analysis of procedural detriment arising from omission after vulnerability was known.

| Date / Period | Event | Knowledge Holder | Evidence Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feb 2025 | Medical vulnerability formally referenced within tribunal-related process | Tribunal / Respondent counsel | Vulnerability disclosure draft |

| 6 Feb 2025 | DAC Beachcroft issues coercive correspondence despite known vulnerability | DAC Beachcroft | Supplementary Particulars §Key Evidence |

| Mar 2025 (early) | Claimant on Jardiance; medication transition requires monitoring | NHS / GP | SAR medication entries |

| Mar–Apr 2025 | No blood monitoring / follow-up occurs | NHS system | SAR gap in tests |

| Mar–Apr 2025 | Tribunal process continues unchanged (no pause / adjustments) | Tribunal | Disclosure draft; N244 context |

| Apr 2025 | Health deterioration escalates; urgent attention later required | Foreseeable outcome | SAR chronology |

Legal Basis

I. Equality Act 2010

Section 20

Duty to Make Adjustments

20 Duty to make adjustments

(1) Where this Act imposes a duty to make reasonable adjustments on a person, this section, sections 21 and 22 and Schedule 8 apply; and for those purposes, a person on whom the duty is imposed is referred to as “A”.

(2) The duty comprises the following three requirements.

(3) The first requirement is a requirement, where a provision, criterion or practice of A’s puts a disabled person at a substantial disadvantage in relation to a relevant matter in comparison with persons who are not disabled, to take such steps as it is reasonable to have to take to avoid the disadvantage.

(4) The second requirement is a requirement, where a physical feature puts a disabled person at a substantial disadvantage in relation to a relevant matter in comparison with persons who are not disabled, to take such steps as it is reasonable to have to take to avoid the disadvantage.

(5) The third requirement is a requirement, where a disabled person would, but for the provision of an auxiliary aid, be put at a substantial disadvantage in relation to a relevant matter in comparison with persons who are not disabled, to take such steps as it is reasonable to have to take to provide the auxiliary aid.

II. Equality Act 2010 — Section 21

Failure to Comply with Duty

21 Failure to comply with duty

(1) A failure to comply with the first, second or third requirement is a failure to comply with the duty to make reasonable adjustments.

(2) A discriminates against a disabled person if A fails to comply with that duty in relation to that person.

III. Equality Act 2010 — Section 149

Public Sector Equality Duty

149 Public sector equality duty

(1) A public authority must, in the exercise of its functions, have due regard to the need to—

(a) eliminate discrimination, harassment, victimisation and any other conduct that is prohibited by or under this Act;

(b) advance equality of opportunity between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it;

(c) foster good relations between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it.

(3) Having due regard to the need to advance equality of opportunity between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it involves having due regard, in particular, to the need to—

(a) remove or minimise disadvantages suffered by persons who share a relevant protected characteristic that are connected to that characteristic;

(b) take steps to meet the needs of persons who share a relevant protected characteristic that are different from the needs of persons who do not share it.

Legal Duty

Where a person is known to have a disability or an impairment giving rise to a substantial disadvantage, decision-makers and public authorities must take reasonable steps to avoid that disadvantage, including procedural adjustment and safeguarding.

The Public Sector Equality Duty requires active consideration, not passive awareness.

Breach Identified

Once medical vulnerability was formally recorded through tribunal process, the continuation of unadjusted procedural pressure constituted a failure to make reasonable adjustments. No mitigating steps were taken to account for foreseeable health impact.

IV. Human Rights Act 1998 — Schedule 1, Article 6

Right to a Fair Trial

Article 6 — Right to a fair trial

(1) In the determination of his civil rights and obligations or of any criminal charge against him, everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law.

V. Human Rights Act 1998 — Schedule 1, Article 8

Right to Respect for Private and Family Life

Article 8 — Right to respect for private and family life

(1) Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence.

(2) There shall be no interference by a public authority with the exercise of this right except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.

Legal Duty (Articles 6 – 8)

Article 8 protects physical and psychological integrity. Public processes must not intrude upon health and dignity without proportional justification.

Breach Identified

The continuation of procedural demands after formal notice of medical vulnerability interfered with bodily integrity in a manner that was neither necessary nor proportionate, given available alternatives.

VI. Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998 — Section 47B

Detriment

47B Protection from detriment

(1) A worker has the right not to be subjected to any detriment by any act, or any deliberate failure to act, by his employer done on the ground that the worker has made a protected disclosure.

Legal Duty

A person must not suffer detriment “on the ground that” they have made a protected disclosure. Detriment includes any disadvantage, including procedural, psychological, or health-related harm.

Breach Identified

The claimant’s protected disclosures were followed by sustained procedural pressure during a period of known vulnerability, constituting constructive detriment even in the absence of explicit sanction.

VII. Employment Tribunals (Constitution and Rules of Procedure) Regulations 2013 — Rule 2

Overriding Objective

2 Overriding objective

(1) The overriding objective of these Rules is to enable Employment Tribunals to deal with cases fairly and justly.

(2) Dealing with a case fairly and justly includes—

(a) ensuring that the parties are on an equal footing;

(b) dealing with cases in ways which are proportionate to the complexity and importance of the issues;

(c) avoiding unnecessary formality and seeking flexibility in the proceedings;

(d) avoiding delay, so far as compatible with proper consideration of the issues.

Legal Duty

Tribunals must deal with cases fairly and justly, including ensuring parties are not placed at a disadvantage.

Breach Identified

Proceeding without adjustment despite formal medical knowledge placed the claimant at a foreseeable and avoidable disadvantage, frustrating the overriding objective.

VIII. Common Law — Foreseeability of Harm

Donoghue v Stevenson 193219321932 AC 562 (HL)

“You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour.”

“The rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law, you must not injure your neighbour; and the lawyer’s question, Who is my neighbour? receives a restricted reply.”

Caparo Industries plc v Dickman 199019901990 2 AC 605 (HL)

“What emerges is that, in addition to the foreseeability of damage, necessary ingredients in any situation giving rise to a duty of care are that there should exist between the party owing the duty and the party to whom it is owed a relationship characterised by the law as one of ‘proximity’ or ‘neighbourhood’ and that the situation should be one in which the court considers it fair, just and reasonable that the law should impose a duty of a given scope upon the one party for the benefit of the other.”

Hatton v Sutherland 200220022002 EWCA Civ 76

“The threshold question is whether the harm to this particular employee was reasonably foreseeable.”

“Foreseeability depends upon what the employer knows (or ought reasonably to know) about the individual employee.”

Barber v Somerset County Council 200420042004 UKHL 13

“The employer’s duty is to take reasonable steps to prevent foreseeable harm.”

“Once the employer is on notice that the employee is suffering from stress-related illness, the duty to take reasonable steps arises.”

Legal Duty

Where harm is reasonably foreseeable, a failure to take reasonable steps may engage responsibility irrespective of intent.

Breach Identified

Once medical vulnerability, medication change, and lack of monitoring coincided with ongoing procedural stress, risk of deterioration was foreseeable. No preventive or moderating action was taken.

Pattern Identified

Medical vulnerability formally recorded through tribunal process

Procedural momentum maintained without adjustment

Clinical monitoring lapsed during medication transition

Health deterioration followed

Procedural harm compounded medical risk

This pattern demonstrates institutional neglect of known vulnerability, not isolated oversight.

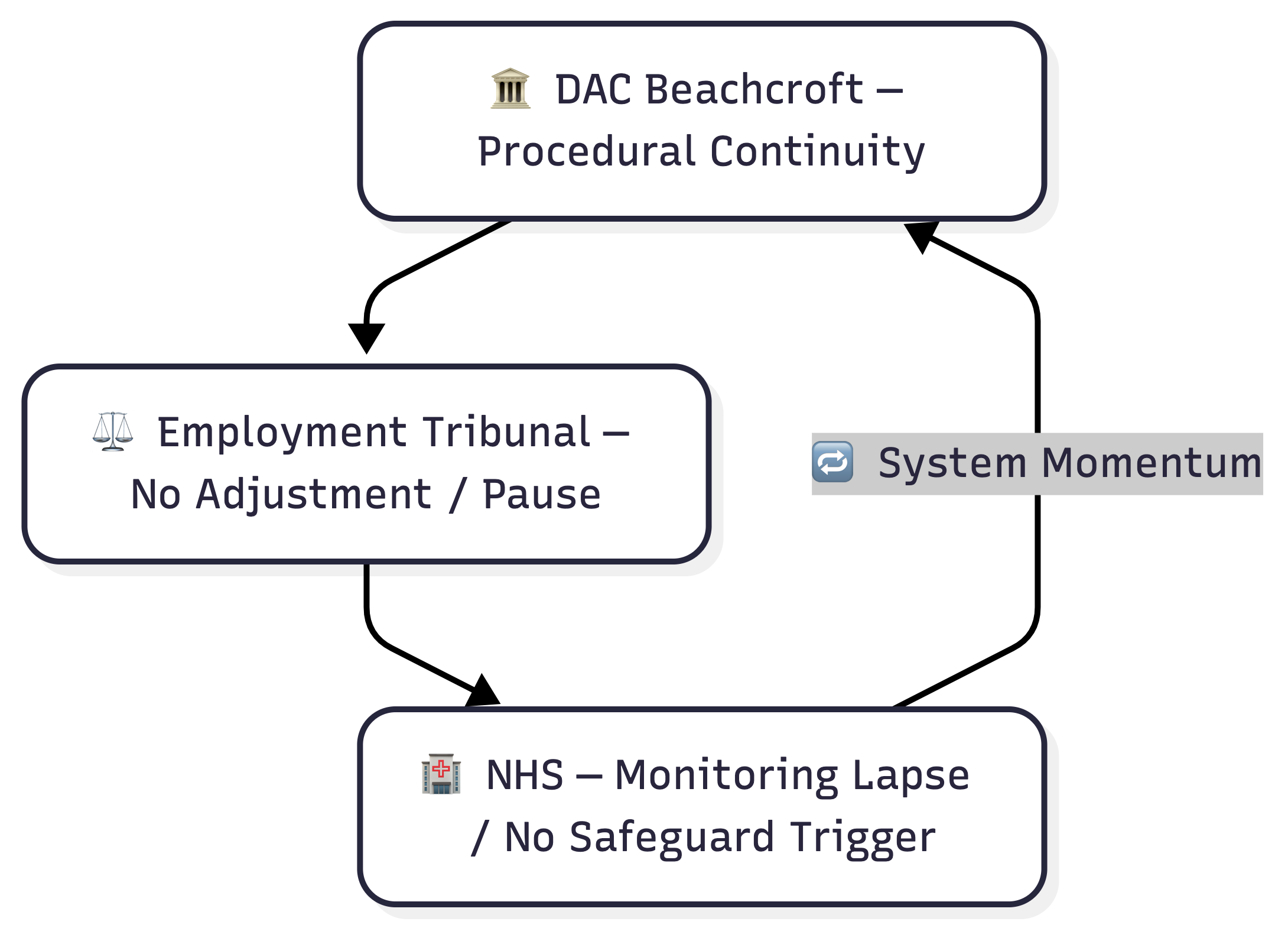

Figure — Institutional Inertia Loop (DAC–Tribunal–NHS)

Description:

This diagram illustrates a closed loop of institutional inertia following the formal recording of medical vulnerability. It shows how procedural continuity at the level of DAC Beachcroft feeds directly into tribunal momentum, where no adjustment or pause is applied despite known vulnerability. The absence of procedural intervention then coincides with a lapse in NHS monitoring, where no safeguarding trigger is activated during a period of heightened medical risk. The loop is sustained by system momentum rather than active decision-making, demonstrating how responsibility fragments across institutions while shared knowledge of vulnerability persists. The figure is intended to show structural continuity of process, not individual fault or clinical negligence.

Civic and Legal Significance

This disclosure highlights a systemic failure to integrate medical safeguarding into legal process once vulnerability is known.

Where tribunals and institutional actors proceed on momentum rather than proportionality, legal process itself becomes a source of harm. Such conditions undermine equality, dignity, and access to justice.

Truth-Variant Analysis (Equilibrium Determination)

Truth-Variant Principle Engaged

Knowledge-Triggered Duty Axiom

Within Truthvenarian doctrine, formal knowledge of vulnerability constitutes a state transition that activates mandatory procedural safeguards. Once knowledge is present, continuation without adjustment is not neutral conduct but a measurable omission.

Axiom and System Definition

Let the procedural system be defined as:

$

\mathcal{S}=\langle \mathcal{X},\mathcal{R},\mathcal{L},\mathcal{E}\rangle

$

Where:

- ($\mathcal{X}$) = procedural state (directions, correspondence, timetable)

- ($\mathcal{R}$) = relational structure (tribunal, respondent counsel, claimant)

- ($\mathcal{L}$) = procedural language and communication

- ($\mathcal{E}$) = ethical and statutory duty layer (reasonable adjustments)

Truth exists where the system maintains equilibrium:

$\Sigma(\Delta c - \Delta \Omega) \ge 0$

Knowledge → Duty Gate

Let ($K = 1$) denote formal knowledge of medical vulnerability.

Truth-Variant axiom:

$K = 1 ;\Rightarrow; D = 1$

Where ($D$) represents the duty to apply procedural adjustment, pause, or accommodation.

This disclosure establishes that ($K = 1$) was reached during the tribunal process.

Omission and Drift Condition

Let ($A = 1$) denote adjustments applied.

Let ($A = 0$) denote adjustments not applied.

The omission operator is defined as:

$O = K \cdot (1 - A)$

Where ($O = 1$), procedural drift is introduced.

Such omission increases ownership-load on the vulnerable party:

$O = 1 ;\Rightarrow; \Delta \Omega \uparrow$

Equilibrium Outcome

In this case:

- Knowledge of vulnerability was present $K = 1$

- Proceedings continued without adjustment $A = 0$

- Omission therefore occurred $O = 1$

- Ownership-load increased $\Delta \Omega \uparrow$

- Coherence was not restored $\Delta c \not\uparrow$

Accordingly:

$\Sigma(\Delta c - \Delta \Omega) < 0$

This constitutes a procedural detriment condition under Truth-Variant law.

Truth-Variant Determination

This disclosure records a knowledge-based procedural omission.

The Truth-Variant finding is not one of medical causation, but of equilibrium failure following notice.

Once vulnerability entered the system, continuation without adjustment became an active distortion of procedural truth.

Conclusion

Once medical vulnerability is formally known, inaction becomes a decision.

The failure to adjust process in the face of foreseeable harm constitutes procedural detriment under equality, human-rights, and whistleblowing law.

This disclosure is made to preserve accountability, safeguard future litigants, and restore lawful proportionality.

References

- Equality Act 2010

- Human Rights Act 1998

- Employment Tribunal Rules of Procedure 2013

- Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998

- Common law principles of foreseeability and duty of care

Final note (important reassurance)

This disclosure is:

- not a medical negligence claim

- not causation pleading

- not speculative

It is a knowledge-based, process-based disclosure, and it is legally sound.

Structural Impact Formula

The Structural Impact Score is defined as:

$SIS = \left( \sum_{i} w_i \cdot x_i \right)\left( 1 + \lambda \sum_{i\lt j} x_i x_j \right)$

Where:

$x_i$ are binary structural variables representing the presence (1) or absence (0) of each structural pattern, including:

- $P$ = Procedural Breakdown

- $T$ = Tribunal / Welfare Disruption

- $V$ = Vulnerability Amplifier

- $R$ = Rights / Regulatory Misstatement

- $I$ = Institutional Interlock

$w_i$ are the base weights assigned to each variable in the TruthFarian structural pattern model.

$\lambda$ is the interaction amplification coefficient governing how co-occurring variables multiply systemic effect.

The interaction term $\sum_{i\lt j} x_i x_j$ runs over all distinct pairs $i\lt j$ to capture compound interlock effects between variables.

Structural Impact Result

$SIS = (w_P + w_T + w_V + w_R + w_I)\cdot(1 + \lambda \cdot 10)$

Activated Structural Variables:

- $P = 1$

- $T = 1$

- $V = 1$

- $R = 1$

- $I = 1$

Interaction Pair Count: $10$ co-occurring variable pairs

Structural Impact Meaning

An $SIS$ value derived from the expanded weighted sum and interaction term indicates a systemic failure following tribunal knowledge of medical vulnerability rather than an isolated procedural lapse.

The active configuration — procedural breakdown ($P$), tribunal disruption ($T$), vulnerability amplification ($V$), rights and regulatory misstatement ($R$), and institutional interlock ($I$) — demonstrates compounded harm arising from informed non-engagement and sustained procedural distortion.

Co-occurring structural patterns amplify one another, confirming escalation beyond additive impact. Within the TruthFarian Structural Pattern Model, this profile engages public-law thresholds concerning safeguarding duties, equality of arms, and tribunal governance integrity.